Organic Chemistry I #

Resources #

Syllabus

Textbook

Study Guide/Solution Manual

Course Information #

Grading #

| Graded Item | % of Final Grade |

|---|---|

| Quizzes | 10% |

| Midterm Exams (2 highest out of 3) | 40% |

| Final Exam | 25% |

| Laboratory Grade | 25% |

Homework is not graded. Quizzes are given randomly during recitation.

Electrons #

Quantum Numbers #

Each electron in an atom is fundamentally unique. But in order for them to be ‘unique,’ they need to have some sort of identity to discern them from other electrons. For electrons, this ‘ID’ is their quantum numbers.

What principle asserts that electrons are unique in an atom?

Make a chart that states the four quantum numbers, what they represent, and their range of possible values.

| Quantum Number | Physical Representation | Possible Values |

|---|---|---|

| Principle ($n$) | size/energy | $1 \rightarrow \infty$ |

| Azimuthal ($\ell$) | shape/orbital | $0 (s), 1 (p), 2 (d), … n$ |

| Magnetic ($m_\ell$) | orientation | $-\ell, … 0, … \ell$ |

| Spin ($m_s$) | spin | $-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}$ |

$\ell$ represents the type of orbital ($s, p, d, f$).

Atomic Orbitals #

The traditional ball model of the atom depicts electrons as particles in space, contained in a discrete sphere. In reality, however, electrons exhibit wave-like behaviours, meaning that they are continuous entities that take up space. There is no hard line that divides electrons and not-electrons. These volumes of space are called ‘orbitals.’

Can there be regions of space with 0 probability of electrons being present? If so, what are they called?

Yes, they’re called nodes.

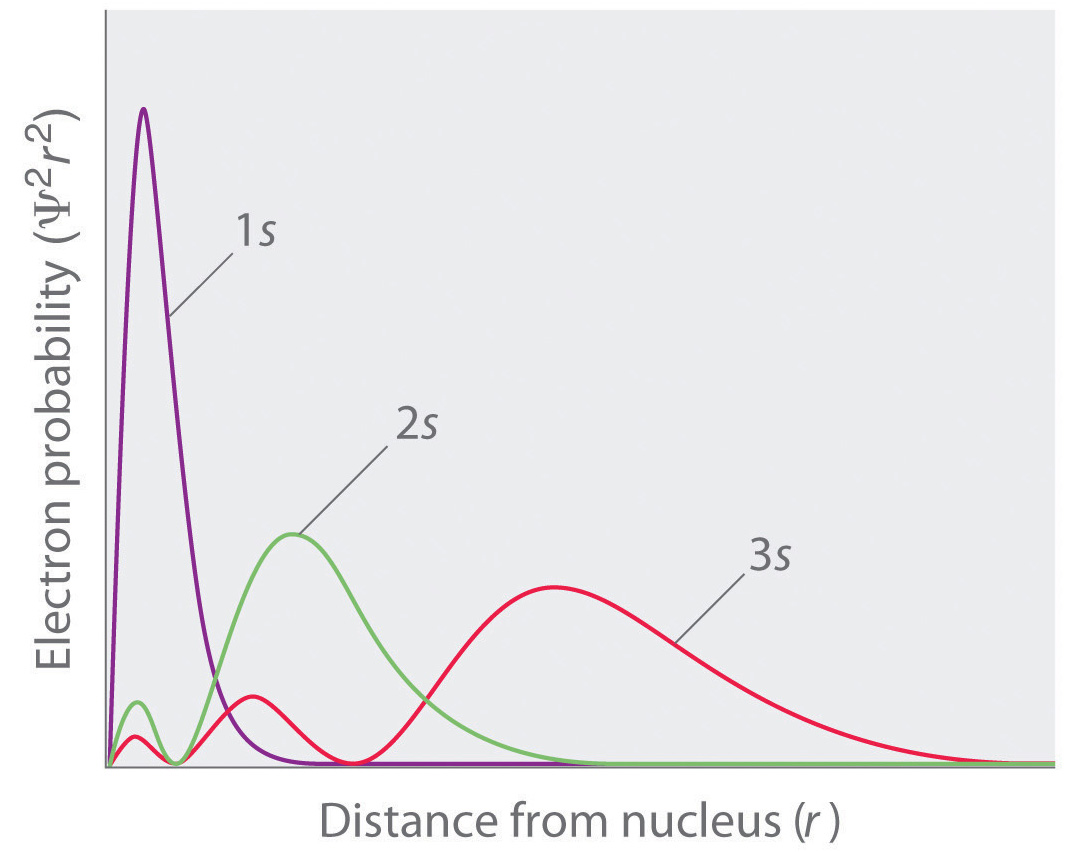

Nodes are not asymptotes! Just because the probability of finding an electron in a region of space approaches zero, that does not mean it equals 0. For example, a $1s$ orbital has no nodes, so all regions of space have a probability to contain the orbital’s electrons, no matter if it is 0.53$\r{A}$ or 500 miles away from the nucleus.

How many nodes are in a 4p orbital?

Three.

The number of nodes in an orbital is equal to $n-1$

Being continuous, the probability distribution is not uniform. What is being varied in these orbitals?

Electron density.

These orbitals/electron density clouds model the probability of an electron occupying a point of space, and their infinitesimal small areas in space come together and form a continuous distribution of volume.

https://tracingcurves.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/46a9d-bohrvs.electroncloud.jpg

What represents orbitals mathematically? (Hint: They are the solutions to Schrödinger’s wave equations.)

Wave functions ($\psi$) and their squares ($\psi^2$).

Regions of space with $\psi^2$ equal to 0 are nodes.

https://cdn.kastatic.org/ka-perseus-images/a5e18b829f12622a749e2f131bd029f8783eaf92.jpg

How many electrons can reside in an orbital? Does it depend on $\ell$?

Two.

Remember, $\ell$ only represents the type of orbital. Yes, we write the maximum number of electrons in an $s$ orbital as $s^2$, and we write the maximum number of electrons in a $p$ orbital as $p^6$, but only when we write the electron configuration. Really, this is just a shorthand, because a $p$ ‘orbital’ is actually three orbitals in disguise, each with their own orientations (those orbitals being $p_x, p_y,$ and $p_z$). Each of these $p_n$ orbitals can hold two electrons.

For a quick formula to get the maximum number of electrons in a type of orbital, you can use the equation $2+4\ell$.

Why can orbitals only have two electrons?

Because of the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

Remember, the PEP states that no two electrons can have the same four quantum numbers. Electrons reside in the same orbital if their $n, \ell,$ and $m_\ell$ are the same as each other. That leaves only the fourth quantum number, $m_s$, which only has two possible values ($-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}$). If there were more than two electrons in an orbital, then it’s guaranteed that there will duplicates, violating the PEP (see the pidgeonhole principle).

Some of you may be disappointed with this explanation, since I don’t really explain why there are only two spin values. Frankly, I do not know, nor do I think it’s something that we’re gonna be expected to know. Though if you can find a reasonably understandable explanation and send it to me, then I’m happy to add it here.

Each orbital has its own distinct shape. For example, $s$ orbitals are ball-like, and $p$ orbitals are dumbbell-shaped.

Electron Configuration #

To represent the amount of electrons in an atom, chemists use electron configurations. We start from a $n$ of 1 and an $\ell$ of 0 ($s$), meaning that hydrogen’s neutral electron configuration is represented as $1s^1$.

The superscripts represent the number of electrons in an orbital. If you add all of them up, you get the number of electrons in the entire atom/ion.

What order do electrons fill orbitals?

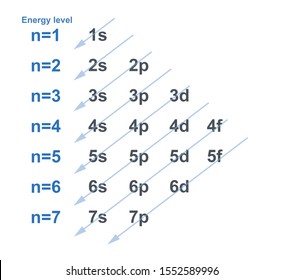

They adhere to the aufbau principle, meaning they fill the orbitals with the lowest orbital energy.

A helpful chart showing the optimal orbital energy path. (https://www.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/chart-electron-configuration-each-energy-level-1552589996)

This diagram is not without its faults. It is generally accurate for the ground states of lower energy atoms, however many exceptions exist with atoms and ions of higher energy.

Additionally, the order that electrons are filled within an orbital type follows Hund’s rule, which states that orbitals with the maximum number of unpaired electrons has the least energy. Remember, electrons within an orbital can have two valid spin states ($-\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}$). Hund’s rule says that instead of filling one orbital completely, electrons fill empty orbitals first and then pair up with already occupied orbitals.

In terms of electron configurations, $1s^22s^22p_x^12p_y^12p_z^1$ is more favorable than $1s^22s^22p_x^22p_y^1$.

What is the electron configuration of $\ce{_{6}C}$?

For longer electron configurations, you can use a shorthand by replacing part of the configuration with the symbol of the noble gas in the previous period. For example, $\ce{_{16}S}$ can be represented as $[\ce{Ne}]3s^23p^4$

What is the electron configuration of $\ce{_{87}Fr}$?

Long form: $1s^22s^22p^63s^23p^64s^23d^{10}4p^65s^24d^{10}5p^66s^24f^{14}5d^{10}6p^67s^1$

Shorthand: $[\ce{Rn}] 7s^1$

The in shorthand form, the $n$ of the $s$ orbital is equal to the period number.

Drawing Molecules #

Lewis Structures #

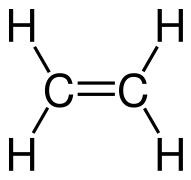

Lewis structures depict the covalent bonds between the valence electrons of atoms. These valence electrons are drawn as dots, and if a dot is between two atomic symbols, that means that it is part of a covalent bond and is shared between those two atoms.

Draw the Lewis structure of $\ce{H2O}$.

Alternatively, you can also depict covalent bonds as lines, with each pair of shared electrons forming parallel lines.

Draw the Lewis structure of ethylene.

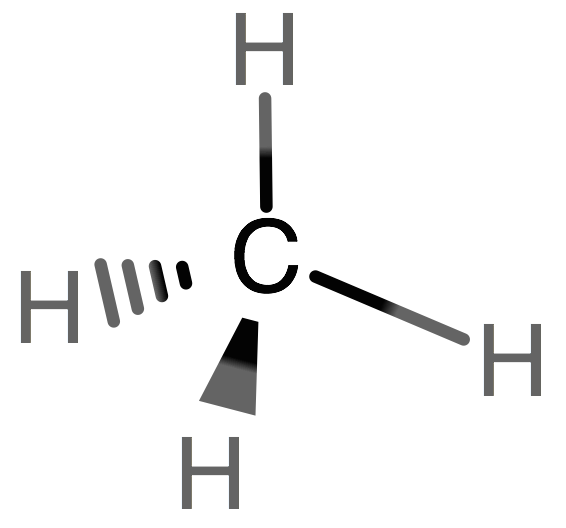

For a more accurate representation of molecules, Lewis structures can depict the general 3D shape of molecules. This can be done by replacing solid lines with dashed wedges for bonds that go into the page, and colored-in wedges for bonds going out of the page.

Draw the Lewis structure of methane in 3D space.

Skeletal Formula #

Drawing everything in a Lewis structure can quickly become a pain, so chemists also utilize skeletal formula form when drawing molecules. Skeletal formulas are like Lewis structures, however they omit non-bonding electrons. Additionally, carbon atoms are the vertices of the diagram, and any hydrogens needed to complete their octets are omitted.

Draw the skeletal formula for decane ($\ce{C10H22}$).

From now on, unless it makes sense to do otherwise, I’ll be using the skeletal formula when drawing molecules in 2D. This is rather inconvenient for me, however, since I have to either make or find a picture depicting the molecule and then potentially cite it. Weirdly enough, I found a library that makes it incredibly easy to show molecules in 3D. It is called 3Dmol.js, and I’ll be using that for the most part.